- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Baseline health-related quality of life (QL) is associated with survival in advanced breast cancer. We sought to identify patients who were less likely to respond to

chemotherapy and at greater risk of toxicity on the basis of their QL. METHODS: We used data from three advanced breast cancer trials in which patients (_n_=378) were treated with

cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluouracil. Patients self-rated their QL using LASA scales for physical well-being (PWB), mood, pain, nausea/vomiting, appetite and overall QL.

Multivariable regression models were constructed to compare overall survival (OS), objective tumour response (OTR), adverse events (AEs) and weight loss according to grouped QL scores.

RESULTS: Physical well-being, mood, appetite and overall QL were significant univariable predictors of OS. Physical well-being and appetite remained significant after adjustment for baseline

biomedical factors. Poor PWB was associated with lower OTR (odds ratio (OR)=0.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09–0.51), higher risk of non-haematological AEs (OR=3.26, 95% CI 1.49–7.15)

and greater risk of weight loss (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.12–5.01) compared with good PWB. CONCLUSION: In women with advanced breast cancer, PWB and appetite are predictors of chemotherapy response

and toxicity as well as survival. Quality of life should be a routine clinical assessment to guide patient selection for chemotherapy and for stratification of patients in clinical trials.

SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE QUALITY OF LIFE INDEX: A PILOT STUDY INTEGRATING TREATMENT EFFICACY AND QUALITY OF LIFE IN ONCOLOGY Article Open access 14 October 2020 PREDICTION

OF QUALITY OF LIFE IN EARLY BREAST CANCER UPON COMPLETION OF ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY Article Open access 13 July 2021 PATIENT-REPORTED FUNCTION, HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE, AND SYMPTOMS IN

APHINITY: PERTUZUMAB PLUS TRASTUZUMAB AND CHEMOTHERAPY IN HER2-POSITIVE EARLY BREAST CANCER Article 07 April 2021 MAIN In advanced breast cancer, the primary goals of treatment are to

prolong and improve quality of life (QL) because the disease is generally incurable. In a pivotal study conducted by Coates et al (1987), patient-rated QL improved significantly on average

in women with advanced breast cancer receiving palliative chemotherapy, and both baseline QL scores and subsequent changes were prognostic for survival (Coates et al, 1992). Although

chemotherapy is effective in relieving cancer-related symptoms, these average benefits may not accrue to all patients and may in some cases be offset by the significant physical and

psychological side-effects. Therefore, appropriate selection of patients for chemotherapy is important to increase the likelihood that its benefits will likely outweigh its harms.

Determination of the prognosis of patients with advanced breast cancer can provide valuable information to guide oncologists in deciding whether to offer palliative chemotherapy. Oncologists

consider a range of patient and disease characteristics such as age, performance status, disease-free interval, hormone receptor status, disease burden and prior adjuvant treatments

(Hortobagyi et al, 1983; Gennari et al, 2005; Largillier et al, 2008). More recently, patient's self-reported health-related QL has also been recognised as predictive of survival (Gotay

et al, 2008; Quinten et al, 2009). Poor QL before treatment is associated with shorter survival in patients with advanced breast cancer (Coates et al, 1992; Efficace et al, 2004; Winer et

al, 2004; Gotay et al, 2008). However, there is only limited evidence of the relationship between baseline QL and response to chemotherapy (Seidman et al, 1995; Kramer et al, 2000; Winer et

al, 2004) and treatment-related toxicity. Investigation of this issue is important because chemotherapy has a narrow therapeutic index and a fine balance between benefits and harms. Such

information might help oncologists and patients to individualise their treatment decisions. In this study, we used data from three trials conducted by the Australian New Zealand Breast

Cancer Trials Group (ANZBCTG) to validate earlier findings that baseline QL predicts overall survival (OS) in advanced breast cancer and investigate the association between baseline QL and

chemotherapy response and toxicity. MATERIALS AND METHODS We used data from the common control arms of three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of first-line chemotherapy for patients with

advanced breast cancer conducted by ANZBCTG (ANZ8101, ANZ8614 and ANZ0001). Trial participants were recruited from participating hospitals across Australia and New Zealand. ANZ8101,

activated in June 1982, was a two-by-two factorial RCT comparing the efficacy of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide _vs_ cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluouracil and prednisone (CMFP),

administered continuously _vs_ intermittently (Coates et al, 1987). ANZ8614, activated in January 1988, was a two-arm RCT comparing the efficacy of mitoxantrone _vs_ CMFP (Simes et al,

1994). ANZ0001, activated in June 2001, was a three-arm RCT comparing the efficacy of intermittent capecitabine _vs_ continuous capecitabine _vs_ CMFP (Stockler et al, 2007). All three

trials included a measurement of patients’ self-reported QL at baseline. Investigation of QL as a predictor of treatment response or toxicity was not specified in the original trial

protocols. PATIENTS Patients had histologically confirmed breast carcinoma with measurable or evaluable recurrent or metastatic disease; adequate bone marrow, hepatic and renal function; and

were available for follow-up. Patients were excluded if they had received cytotoxic chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic disease or extensive radiotherapy, or had a history of other

cancer, diabetes mellitus or cardiac failure. Only patients assigned to the continuous CMFP in each of the three trials were included in the present analysis. Patients assigned to the

intermittent CMFP arm of ANZ8101 were excluded from this study because this treatment arm was inferior to the CMFP regimen given continuously as in the other trials. All patients provided

written informed consent for participation in the trials. TREATMENTS In each of the three trials, CMFP was administered in 28-day cycles with oral cyclophosphamide (100 mg m−2) daily for 14

days; intravenous methotrexate (40 mg m−2) and intravenous 5-fluorouracil (600 mg m−2) on days 1 and 8. Oral prednisone (40 mg m−2) for first 14 days was routinely administered in patients

from ANZ8101 and ANZ8614, and was optional in ANZ0001. All patients continued the initial chemotherapy regimen until disease progression, intolerance or unacceptable toxicity. Therapy beyond

disease progression was at the discretion of the treating oncologist. QL INSTRUMENTS Patients self-reported their QL with five linear analogue self assessment (LASA) scales that measured

physical well-being (PWB), mood, pain, nausea/vomiting and appetite (Priestman et al, 1977; Coates et al, 1993), and a single summative LASA scale that measured overall QL (Spitzer et al,

1981). All scales were 100 mm long and scores range from 0 (best) to 100 (worst). For the purpose of our analysis, scores for each QL scale were arbitrarily divided into three groups: good

(0–25), mid (26–65) or poor (66–100). The categorisation was selected to be consistent with the cut-points used in a previous study (Coates et al, 1992). TREATMENT BENEFITS Treatment

benefits were evaluated by measuring OS, progression-free survival (PFS), objective tumour response (OTR) and improvement in baseline body weight. OS and PFS were measured from randomisation

to the date of death or first documented disease progression respectively. OTR rate was measured as the proportion of patients with evaluable disease who achieved a complete response (CR)

or partial response (PR). Weight loss (_vs_ stable or weight gain) was measured as the proportion of patients with an average decrease in weight from their baseline reading. TREATMENT

TOXICITY Adverse events (AEs) were expressed as the proportion of patients who developed any grade 3 or grade 4 toxicity during the first 4 cycles of chemotherapy treatment. World Health

Organisation criteria (Miller et al, 1981) were used for ANZ8101 and ANZ8614; National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (Arbuck et al, 1998) were used for ANZ0001. Haematological

(anaemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) and non-haematological (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, stomatitis and alopecia) AEs were analysed separately. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Overall survival

and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between patients with good, mid and poor levels for each QL scale at baseline were compared with the log-rank test (Kaplan

and Meier, 1958). Cox proportional-hazard models were used to estimate differences in OS according to each level of the QL scale (Cox, 1972). Multivariable analysis for OS was first

performed with backward stepwise selection of biomedical variables only. Then, multivariable analysis for OS was repeated with backward stepwise selection of biomedical and QL variables.

Only statistically significant variables (_P_<0.05) were retained in the final multivariable models. As shown in a previous analysis using the same data set (Lee et al, 2010), trial is a

significant factor for survival; thus we stratified for trial in all univariable and multivariable analyses for this study. Formal tests to detect the presence of collinearity between the

different QL scales, and QL scales and ECOG performance status were also performed (Weissfeld, 1989). Univariable analyses with logistic regression tested for associations between QL

subscales and OTR, AE and weight loss. Multivariable models for these outcomes were constructed to estimate the effects of these QL subscales, adjusted for biomedical variables found to be

significant in Cox model for OS. All analyses were two-sided with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. No imputation of missing baseline QL values was performed. RESULTS BIOMEDICAL AND

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS A total of 378 patients with a median follow-up of 4.8 years were included in this pooled analysis. The number of patients from ANZ8101, ANZ8614 and ANZ0001 were

75 (20%), 194 (51%) and 109 (29%), respectively. The median follow-up of these patients from ANZ8101, ANZ8614 and ANZ0001 were 4.8 years (range 0–4.8 years), 10.1 years (range 0–10.9 years)

and 3.2 years (range 0–4.8 years), respectively. Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics and the treatment profiles of these patients for the overall cohort and according to the

baseline PWB. Apart from performance status and lung metastasis, distribution of baseline characteristics was similar in patients with good, mid and poor PWB. Similar patterns of baseline

characteristics were observed for other QL scales (data not shown). BASELINE QL SCORES Baseline LASA scores for each QL scale were available for 89–94% of the patients. The proportion of

patients with self-rating for each scale was 93% (PWB), 94% (mood), 93% (pain), 93% (nausea and vomiting), 93% (appetite) and 89% (overall life quality). The distribution of the three

categories of LASA scores for each QL subscale is shown in Table 2B. CMFP TREATMENT Two patients randomised to CMFP chemotherapy in the original trials did not receive the assigned

treatment. The remaining 376 patients (99.5%) received a median five cycles of treatment. The chemotherapy doses administered were between 90 and 93% of those planned. Patients with good,

mid and poor PWB received medians of 6, 5 and 3 cycles of CMFP, respectively (Table 1). OS AND PFS Physical well-being, mood, appetite and overall QL were predictors of OS in the univariable

analyses (Table 2B). Physical well-being and appetite were independent predictors of survival in a multivariable model with biomedical and QL variables (Table 3B). Performance status was

statistically significant in a multivariate model with biomedical factors only (Table 3A), but was not statistically significant in a multivariable model with biomedical and QL scales (Table

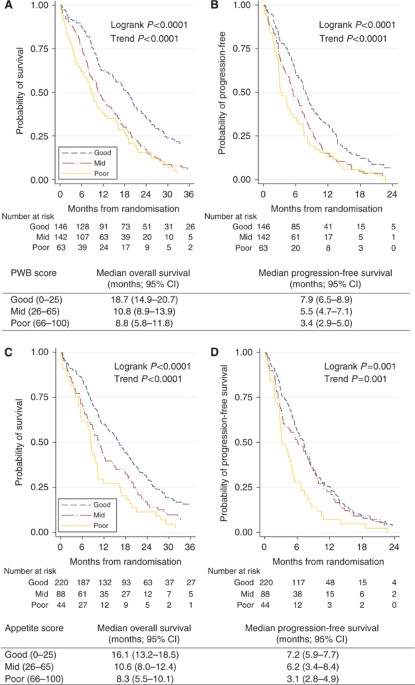

3B). Patients with good PWB at baseline had a statistically significantly longer PFS and OS compared with patients who had mid or poor PWB (Figure 1A and B). The median OS for patients with

good, mid and poor PWB were 19, 11 and 9 months, respectively (log-rank _P_<0.0001). Similar results were observed for patients with good, mid and poor appetite (Figure 1C and D).

Significant collinearity was not detected between the different QL scales or between QL scales and ECOG performance status (results not shown). OBJECTIVE TUMOUR RESPONSE The OTR rates for

patients with good, mid and poor PWB were 47, 32 and 18%, respectively (adjusted _P_trend<0.001; Figure 2A). For patients with good, mid and poor appetite, the OTR rates were 41, 34 and

18% respectively (adjusted _P_trend=0.02; Figure 2A). WEIGHT LOSS Fifty-one percent of women experienced weight loss during chemotherapy. Women with good PWB had a mean weight gain during

chemotherapy of 2%, but mean weight loss was 2% for women with mid PWB and 4% for women with poor PWB, respectively (adjusted _P_trend=0.01; Figure 2B). For women with good appetite, there

was a mean weight gain of 0.5%, but mean weight loss was 2% for women with mid appetite and 7% for women with poor appetite (adjusted _P_trend=0.006; Figure 2B). TREATMENT TOXICITY

Non-haematological AE rates were statistically significantly different for patients with good (16%), mid (31%) and poor (38%) PWB (adjusted _P_trend=0.002; Figure 2C). Grade-3 or 4 nausea

and vomiting were reported in 19, 41 and 42%; diarrhoea in 9, 12 and 11%; and grade-3 and 4 stomatitis in 8, 11 and 17% of patients with good, mid and poor PWB, respectively. Grade-3 and 4

alopecia rates were similar in the three PWB groups. The rates of non-haematological AEs were not significantly different in patients with good, mid and poor appetite (adjusted

_P_trend=0.06; Figure 2B). Grade-3 and 4 haematological toxicity rates were not associated with PWB (adjusted _P_trend=0.92) or appetite scores (adjusted _P_trend=0.60). DISCUSSION In this

analysis of women treated with CMFP as first-line chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer, patient self-reported PWB and appetite at baseline were independent predictors of OS and PFS. Women

with poor PWB had a median OS that was 10 months shorter, and a median PFS that was 5 months shorter, than women with good PWB. Furthermore, women with poor PWB had OTR rates 29% lower,

weight loss rates 19% lower and treatment-related non-haematological AE rates 22% higher than women with good PWB. Similar findings were observed for women with poor appetite compared with

those who had good appetite. Our study also showed that women with poor QL derived less benefit and experienced more toxicity when treated with chemotherapy than women with good QL. Overall,

women reporting poor QL at baseline received 50% fewer cycles of chemotherapy, were 20–30% less likely to benefit from chemotherapy and experienced rates of non-haematological treatment

toxicity 20% higher than women reporting good QL at baseline. This research adds to the growing evidence that QL is an independent predictor of survival in advanced cancer. In a systematic

review of cancer trials, Gotay et al (2008) reported that 36 of 39 trials showed an association between QL and survival. Specific QL measures most frequently identified in these trials were

overall QL, physical well being, appetite loss and pain. Another meta-analysis using data from 30 cancer trials produced a multivariable model that identified impaired physical functioning,

pain and appetite loss as independent predictors of survival in addition to established biomedical factors (Quinten et al, 2009). Individual trials in advanced breast cancer have shown

similar findings with PWB (Coates et al, 1992), appetite loss (Efficace et al, 2004), pain (Kramer et al, 2000) and overall QL (Seidman et al, 1995; Winer et al, 2004) all reported as

independent predictors of survival. This study validates the prognostic significance of self-reported QL, and specifically of PWB and appetite, as predictors of survival in advanced breast

cancer. Furthermore, our findings raise the important question of whether measurement of baseline QL can be used to improve the selection of patients for chemotherapy. To date, few studies

have investigated baseline QL as predictor of treatment benefit and/or toxicity in advanced breast cancer. Kramer et al (2000) reported an association between QL (dyspnoea, fatigue and

overall QL) and tumour response in their analysis of 187 women treated with paclitaxel or doxorubicin, but selection of specific QL scales as independent predictors in the final

multivariable model was reported as unstable because of multi-collinearity. They did not examine associations between QL and toxicity in this analysis. Two other studies reported no

association between QL and tumour response to chemotherapy (Seidman et al, 1995; Winer et al, 2004) or treatment-related toxicity (Seidman et al, 1995). Possible explanations for the

differences between these results and our study include small sample size (Seidman et al, 1995), the type of QL instruments and QL subscales used, and the methods used to assess tumour

response. The main strength of this study is the use of high-quality, individual patient data from three successive randomised clinical trials conducted by the same group. The pooled data

set contains well-documented demographic, clinical and QL characteristics of trial participants who were treated with the same regimen of chemotherapy. Women in this study were assigned

chemotherapy independent of their baseline QL. Follow-up and outcome data were collected prospectively with rigorous quality control. This study has several limitations. First, our findings

are from women with advanced breast cancer who were treated with CMFP. They may differ with other chemotherapy regimens or for other cancers (Quinten et al, 2009). Second, the results are

not generalisable to women with early-stage breast cancer who do not have tumour-related symptoms (Coates et al, 2000; Goodwin et al, 2004; Gotay et al, 2008). Finally, this analysis was

conducted _post hoc_ using available trial data and therefore should be regarded as hypothesis-generating for future studies, rather than definitive. If our findings are confirmed, trials of

new treatment approaches should be investigated for women with poor QL. These trials could address the value of any chemotherapy _vs_ none, of less intense _vs_ standard-intensity

chemotherapy, or of chemotherapeutic or biological agents with a more favourable therapeutic–toxic ratio. Outcomes, which incorporate both survival time and QL, such as quality-adjusted PFS

and OS, may be more relevant measures of treatment benefit in these women. The results of this study also suggest the value of stratifying patients by their baseline QL for future randomised

trials in advanced breast cancer. The primary goal of chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer is to prolong and improve QL. Our findings suggest that women with poor QL derive less benefit

from chemotherapy and have increased risks of toxicity than women with good QL. This analysis should be regarded as hypothesis-generating and future studies that examine the role of

chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer patients with poor QL are warranted. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 16 NOVEMBER 2011 This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to

Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication _ REFERENCES * Arbuck S, Ivy S, Setser A (1998) The Revised Common Toxicity Criteria: Version 2.0: CTEP Website.

http://ctep.info.nih.gov * Coates A, Gebski V, Bishop J, Jeal P, Woods R, Snyder R, Tattersall M, Byrne M, Harvey V, Gill G (1987) Improving the quality of life during chemotherapy for

advanced breast cancer. A comparison of intermittent and continuous treatment strategies. _N Engl J Med_ 317: 1490–1495 Article CAS Google Scholar * Coates A, Gebski V, Signorini D,

Murray P, McNeil D, Bryne M, Forbes J (1992) Prognostic value of quality-of-life scores during chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. _J Clin Oncol_ 10: 1833–1838 Article CAS Google

Scholar * Coates A, Thomson D, McLeod G, Hersey P, Gill PG, Olver IN, Kefford R, Lowenthal RM, Beadle G, Walpole E (1993) Prognostic value of quality of life scores in a trial of

chemotherapy with or without interferon in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma. _Eur J Cancer_ 29A: 1731–1734 Article CAS Google Scholar * Coates AS, Hurny C, Peterson HF,

Bernhard J, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A (2000) Quality-of-life scores predict outcome in metastatic but not early breast cancer. _J Clin Oncol_ 18: 3768–3774 Article CAS

Google Scholar * Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life-tables. _J Royal Stat Soc_ 34: 187–220 Google Scholar * Efficace F, Biganzoli L, Piccart M, Coens C, Van Steen K, Cufer T,

Coleman RE, Calvert HA, Gamucci T, Twelves C, Fargeot P, Bottomley A (2004) Baseline health-related quality-of-life data as prognostic factors in a phase III multicentre study of women with

metastatic breast cancer. _Eur J Cancer_ 40: 1021–1030 Article CAS Google Scholar * Gennari A, Conte P, Rosso R, Orlandini C, Bruzzi P (2005) Survival of metastatic breast carcinoma

patients over a 20-year period. _Cancer_ 104: 1742–1750 Article Google Scholar * Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Bordeleau LJ, Pritchard KI, Trudeau ME, Koo J, Hood N (2004) Health-related quality of

life and psychosocial status in breast cancer prognosis: analysis of multiple variables. _J Clin Oncol_ 22: 4184–4192 Article Google Scholar * Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, Efficace

F (2008) The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. _J Clin Oncol_ 26: 1355–1363 Article Google Scholar * Hortobagyi G, Smith T, Legha S,

Swenerton K, Gehan E, Yap H, Buzdar A, Blumenschein G (1983) Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer. _J Clin Oncol_ 1: 776–786 Article CAS Google Scholar

* Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. _J Am Stat Assoc_ 53: 457–481 Article Google Scholar * Kramer JA, Curran D, Piccart M, de Haes JCJM,

Bruning P, Klijn J, Van Hoorebeeck I, Paridaens R (2000) Identification and interpretation of clinical and quality of life prognostic factors for survival and response to treatment in

first-line chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer. _Eur J Cancer_ 36: 1498–1506 Article CAS Google Scholar * Largillier R, Ferrero J-M, Doyen J, Barriere J, Namer M, Mari V, Courdi A,

Hannoun-Levi JM, Ettore F, Birtwisle-Peyrottes I, Balu-Maestro C, Marcy PY, Raoust I, Lallement M, Chamorey E (2008) Prognostic factors in 1038 women with metastatic breast cancer. _Ann

Oncol_ 19: 2012–2019 Article CAS Google Scholar * Lee CK, Lord SJ, Stockler MR, Coates AS, Gebski V, Simes RJ (2010) Historical cross-trial comparisons for competing treatments in

advanced breast cancer – an empirical analysis of bias. _Eur J Cancer_ 46: 541–548 Article CAS Google Scholar * Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A (1981) Reporting results of

cancer treatment. _Cancer_ 47: 207–214 Article CAS Google Scholar * Priestman T, Baum M, Jones V, Forbes J (1977) Comparative trial of endocrine versus cytotoxic treatment in advanced

breast cancer. _Br Med J_ 1: 1248–1250 Article CAS Google Scholar * Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MAG, Cleeland C, Osoba D, Bjordal K, Bottomley A (2009) Baseline

quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. _Lancet Oncol_ 10: 865–871 Article Google Scholar * Seidman

AD, Portenoy R, Yao T-J, Lepore J, Mont EK, Kortmansky J, Onetto N, Ren L, Grechko J, Beltangady M, Usakewicz J, Southrada M, Houston C, McCabe M, Salvaggio R, Thaler H, Norton L (1995)

Quality of life in phase II trials: a study of methodology and predictive value in patients with advanced breast cancer treated with paclitaxel plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. _J

Natl Cancer Inst_ 87: 1316–1322 Article CAS Google Scholar * Simes R, Gebski V, Coates A, Forbes J, Harvey V, Van Hazel G, Tattersall M, Abdi E, Brigham B (1994) Quality of life with

single agent mitozantrone or combination chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer, a randomised trial. _Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol_ 13: 73 Google Scholar * Spitzer W, Dobson A, Hall J,

Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, Battista RN, Catchlove BR (1981) Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL index for use by physicians. _J Chronic Dis_ 34: 585–597

Article CAS Google Scholar * Stockler M, Sourjina T, Harvey V, Frances P, Byrne M, van Hazel G, Fitzharris B, Ackland S, Finch K, Lindsay D, Kato-Fong A, Paksec L, Gebski V, Simes R,

Coates A, Forbes J (2007) A randomized trial of capecitabine given intermittently versus continuously versus classical CMF as first line chemotherapy for women with advanced breast cancer

unsuited to more intensive treatment. _Breast Cancer Res Treat_ 100: S278 Google Scholar * Weissfeld LA (1989) A multicollinearity diagnostic for models fit to censored data. _Commun Stat

Theory Methods_ 18: 2073–2085 Article Google Scholar * Winer EP, Berry DA, Woolf S, Duggan D, Kornblith A, Harris LN, Michaelson RA, Kirshner JA, Fleming GF, Perry MC, Graham ML, Sharp SA,

Keresztes R, Henderson IC, Hudis C, Muss H, Norton L (2004) Failure of higher-dose paclitaxel to improve outcome in patients with metastatic breast cancer: cancer and leukemia group B trial

9342. _J Clin Oncol_ 22: 2061–2068 Article CAS Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, The University of Sydney,

Camperdown, NSW, Australia C K Lee, M R Stockler, A S Coates, V Gebski, S J Lord & R J Simes * Sydney Cancer Centre – Royal Prince Alfred and Concord Hospitals, Sydney, NSW, Australia M

R Stockler & R J Simes * International Breast Cancer Study Group, Bern, Switzerland A S Coates Authors * C K Lee View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * M R Stockler View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * A S Coates View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * V Gebski View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * S J Lord View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * R J Simes View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONSORTIA ON BEHALF OF AUSTRALIAN NEW ZEALAND BREAST CANCER

TRIALS GROUP CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to C K Lee. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Lee, C., Stockler, M., Coates, A. _et al._ Self-reported health-related quality of life is an independent predictor of chemotherapy treatment benefit and toxicity

in women with advanced breast cancer. _Br J Cancer_ 102, 1341–1347 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605649 Download citation * Received: 23 December 2009 * Revised: 13 March 2010 *

Accepted: 17 March 2010 * Published: 13 April 2010 * Issue Date: 27 April 2010 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605649 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will

be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * quality of life * advanced breast cancer * treatment benefits * treatment toxicity