- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

I didn't realize I was so close to one National Guard company — maybe 50 yards. The National Guard got into a V formation. I heard two cracks — unmistakable rifle shots. Before I knew

it, I was on the ground, struck on the left heel. The rounds were going off over my head. I tried to raise my head to see where I was hit. Someone yelled. It was my roommate, Alan Canfora.

“Stay down! Stay down! It's bird shot,'’ he yelled. Fortunately, I already was on the ground wounded— that was the good news — instead of upright and running. After 13 seconds,

they stopped firing. It seemed like an eternity. Sixty-plus rounds were fired. There were National Guardsmen that day that were horrified. About 75 of them on the hillside did not fire. Or,

if they did fire, they did into the air. Mike Brock, a Kent State football player, found me. “Buddy, we're gonna get you out of here.'’ He threw me over his body and carried me

across the parking lot. Back in the dorm, I remember girls screaming. One applied a tourniquet to my leg. I was placed on a gurney and wheeled into an ambulance. A wounded girl already was

in the ambulance —Sandy [Scheuer, who died en route to the hospital]. That was a bad situation. At the hospital, my pain worsened. A lot of damage was done to my foot. My mother had been a

nurse. She came [to Kent State from out of town] and convinced the surgeon to try to save the foot. They did. I spent 13 days in the hospital. JOHN CLEARY A 19-YEAR-OLD STUDENT THEN, CLEARY

WAS SHOT IN THE CHEST BUT RECOVERED FROM HIS WOUNDS. TODAY HE LIVES IN GIBSONIA, PENNSYLVANIA. Through the grapevine, I knew there was a rally and that the National Guard was there. I went

there out of curiosity; it wasn't my thing. I was kind of oblivious to all of the anti-war protests. With my family's military background, I looked at soldiers as professionals. It

never dawned on me that they would shoot unarmed students. I had no fear anything would happen. I expected them to do the right thing, to maintain order. I borrowed my roommate's

camera. I was observing, when it was announced this was an illegal rally. Tension built. There was tear gas, a lot of obscenities and a few rocks thrown. But thousands were merely observing.

I felt that had the National Guard held its ground, the protest would have run its course. We would have moved on, probably to our next class. Or, if they had shot into the air, I believe

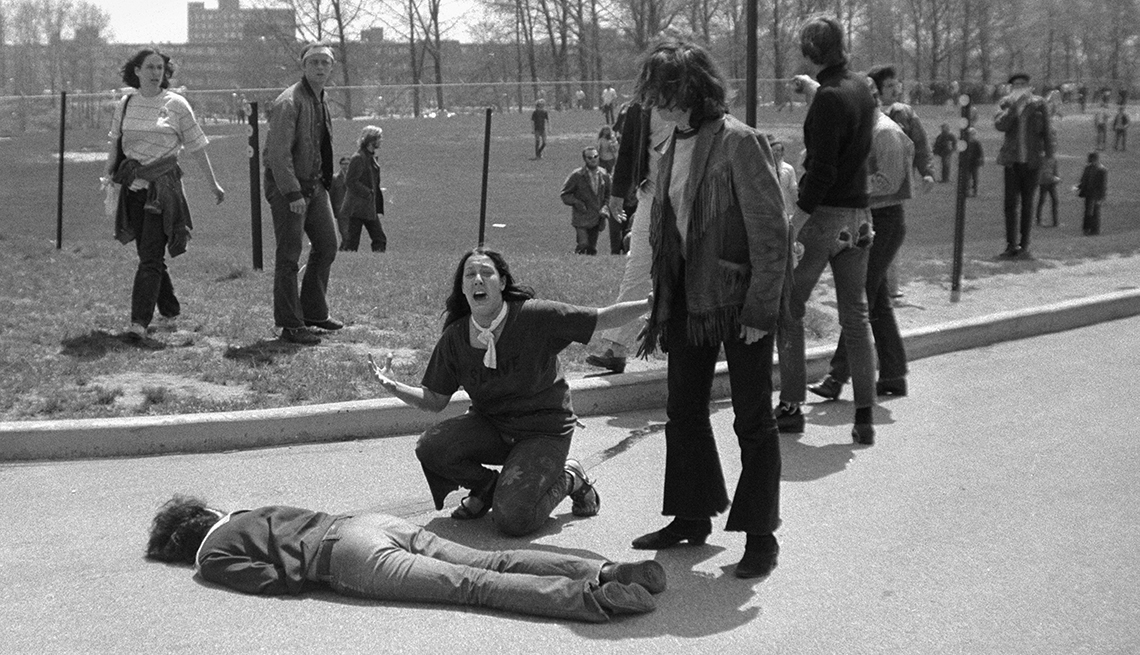

students would have dispersed. Anti-war demonstrators at Kent State University run as National Guardsmen fire tear gas and bullets into the crowd. Bettman/Getty Images The National Guard

took a different tact. The troops walked by me to the practice football field. They knelt, aimed their rifles into the crowd, then stood up and retreated to the hill. I thought it was

winding down. There was no threat to the guard at that point. I thought I'd get one more picture. I was about 100 feet away from the guard. I started to swing my camera to take a

picture, when I was hit in the chest by gunfire. It felt like a sledgehammer. Next thing I knew, I was in the hospital. If the bullet had been a couple of inches one way or the other, I

wouldn't be here. I was 19. I still have metal fragments in my body. RON SNYDER A 33-YEAR-OLD OFFICER IN THE NATIONAL GUARD THEN, SNYDER WAS CAPTAIN OF HIS UNIT, BUT IT WAS NOT INVOLVED

IN THE SHOOTINGS. TODAY HE LIVES IN ROOTSTOWN, OHIO. I was there and saw it all. Our job is to provide brutal force. These were not demonstrators — these were rioters. There was a lot of

commotion, for lack of a better word. Two nights earlier, they burned the ROTC building to the ground. Man, the sky was aglow. The only thing left was charcoal. From the highway, it looked

as if someone firebombed the city of Kent. We woke Sunday, May 3, and restocked our tear gas for the grenade launchers. We had used them in Akron during the 1968 racial riots. That is where

I got the nickname “Capain Gas.'’ My object with tear gas was to prevent personal confrontation. We know that if we are eyeball to eyeball, somebody's going to get hurt. We got an

intelligence update — people were coming in from out of town. We were told some had machine guns. That night, there were roughly 1,000 to 2,000 people at the corner of campus. They started

making a problem. We had armored vehicles and a helicopter — the idea was a show of force. Brig. Gen. Robert Canterbury was on the scene. He was a World War II veteran, a stern guy. We were

told that there would be a mass arrest at the dormitories. After being read the riot act, they destroyed everything in sight. I was in charge of 60 to 80 troops. I could see students (inside

the dormitory) fighting amongst themselves — fistfights. My concern was that I knew that if I turned my company loose, there was going to be a lot of hurt and blood. The next morning, May

4, we received intelligence updates. They sounded really bad. More people were coming from other cities. I sensed there were hostile people there. Just before noon, things started turning

worse. Canterbury and the police decided to disperse them. Tear gas was used first. Some protestors picked up the canisters and threw them back. As they became more disorderly, they were

again ordered to leave the Commons. They did not leave. It becomes a riot then. The students were nasty and threatening. The general said, “If they attack, you're going to have to

shoot." One company was going to swing around the architecture building and push them that way. We were to block our side. We took position between two buildings. I was unable to see

the other company moving up the hill. I saw a surge of students running toward the guard. Then the firing started. A bullet struck a building to my left and concrete flew off. I backed up. I

didn't know what was happening. I saw some students fall. I got on the radio and called for ambulances. My thought was, Who is shooting and where is it coming from? I didn't know

who did the shooting. I checked everybody's weapons in my company to ensure they had not been fired. Our company moved out to see who was alive and who was dead, and if anybody could be

helped. The dead were dead; the others were helped by students. There was nothing else I could do. I heard nothing like [a command to fire]. There was no order. If one guy shoots, another

trooper is coming behind him [to shoot]. I am not defending anybody. But if one guy shoots, they're all gonna shoot. I can tell you that, based on what I have read, every guy who fired

thought his life was in danger.