- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

NEWGATE PRISON, LONDON, 1840 This part of London was like no place Evangeline had ever seen. The air, dense with coal smoke, reeked of horse manure and rotting vegetables. Women in tattered

shawls loitered under oil lamps, men huddled around barrel fires, children — even at this late hour — darted in and out of the road, picking through rubbish, shrieking at each other,

comparing finds. Evangeline squinted, trying to make out what they had in their hands. Was it — ? Yes. _Bones_. She'd heard about these children who earned pennies collecting animal

bones that were turned to ash and mixed with clay to make the ceramics displayed in ladies’ china cupboards. Even a few hours ago she might've felt pity; now she only felt numb.

"There she is,” one of the constables said, gesturing out the window. “The Stone Jug." "Stone Jug?” Evangeline leaned forward, craning her neck. “Newgate.” He smirked. “Your

new home." In tawdry penny circulars she'd read stories about the dangerous criminals locked up in Newgate. Now here it was, a block-long fortress squatting in the shadow of St.

Paul's Cathedral. As they drew closer Evangeline saw that the windows facing the street were strangely blank. It wasn't until the coachman shouted at the horses and pulled hard on

the reins in front of the tall black gates that she realized the windows were false, painted over. A small crowd, idling near the entrance, swarmed the carriage. “Misery mongers,” said the

constable with the droopy moustache. “The show never gets old." The three constables filed out of the carriage, barking at the crowd to stand back. Evangeline crouched in the cramped

compartment until one of them gestured impatiently. “Come on!” She hobbled to the lip of the door and he tugged at her shoulder. When she stumbled out of the carriage, he hoisted her like a

sack of rice and dumped her on the ground. Her cheeks burned with shame. Large-eyed children and sour-faced adults stared as she found her footing. “What a disgrace,” a woman spat. “God have

mercy on your soul." A constable pushed Evangeline toward the iron gates, where their small group was met by two guards. As she shuffled through the entry, flanked by the guards, the

constables behind, she gazed up at the words inscribed on a sundial above the arch. _Venio Sicut Fur_. Most of the prisoners passing through these gates probably didn't know their

meaning, but Evangeline did. _I come as a thief_. * The gate clanged shut. She heard a muffled noise, like cats mewling in a bag, and cocked her head. “The rest of the harlots,” a guard told

her. “You'll be with ‘em soon enough." Harlots! She cringed. A slight man with a large ring attached to his belt, keys hanging from it like oversized charms, was hurrying toward

them. “This way. Only the prisoner and two of ye." Evangeline, the constable with the droopy moustache, and one of the guards followed him into a vestibule and up several flights of

stairs. She moved slowly in the leg irons; the guard kept prodding her in the back with a baton. They made their way through a twisting maze of corridors, dimly lit by oil lanterns that hung

from the thick stone walls. The turnkey came to a stop in front of a wooden door with two locks. Riffling through the keys, he found the one he was looking for and inserted it in the top

lock, then in the lock below. He pushed the door open into a small room with only an oak desk and chair, lighted by a lamp high on the wall, and crossed the room to knock on another, smaller

door. "Beg your pardon, Matron. A new prisoner.” Silence. Then, faintly, “Give me a moment." They waited. The men leaned against a wall, talking among themselves. Evangeline stood

uncertainly in her chains in the middle of the room. Her underarms were damp, and the irons chafed her ankles. Her stomach rumbled; she hadn't eaten since morning. After some time, the

door opened. The matron had clearly been woken up. Her angular face was heavily lined, her graying hair pulled back in a messy bun. She wore a faded black dress. “Let's get on with

it,” she said irritably. “Has the prisoner been searched?” "No, ma'am,” the guard said. She waved toward him. “Go to." Roughly he ran his hands over Evangeline's

shoulders, down her sides, under her arms, even, quickly, between her legs. She pinked with embarrassment. When he gave the matron a nod, she made her way to the desk, lit a candle, and sank

into the chair. Opening a large ledger filled with lines of tiny script, she said, “Name." "Evangel—" "Not you,” the matron said, without looking up. “You have forfeited

your right to speak." Evangeline bit her lip. The constable extracted a piece of paper from the inner pocket of his waistcoat and peered at it. “Name is . . . ah . . . Evangeline

Stokes." She dipped her quill into a pot of ink and scratched on the ledger. “Married?" "No." "Age." "Ah . . . let's see. She'll be twenty-two.”

"She will be, or she is?" "Born in the month of August, it says here. So . . . twenty- one." The matron looked up sharply, her pen poised over the paper. “Speak

precisely, constable, or we'll be here all night. Her offense. In as few words as possible." He cleared his throat. “Well, ma'am, there's more than one.” "Start with

the most egregious." He sighed. “First . . . she's an accused felon. Of the worst kind." "The charge.” “Attempted murder." The matron raised a brow at Evangeline.

"I didn't—” she started. The matron held out the flat of her hand. Then she looked down, writing in the ledger. “Of whom, constable." "A chambermaid employed by . . . aah”

— he searched the paper — “a Ronald Whitstone, address 22 Blenheim Road, St. John's Wood." "By what method." "Miss Stokes pushed her down the stairs.” She looked

up. “Is the victim . . . all right?" "Seems to be. Shaken, but essentially . . . all right, I suppose." Out of the corner of her eye, Evangeline saw a small movement where the

floor met the wall: a thin rat squirming out of a crack in the baseboard. "And what else?" "An heirloom belonging to the owner of the house was found in Miss Stokes's

room." "What kind of heirloom?" "A ring. Gold. With a valuable gemstone. A ruby.” "It was given to me,” Evangeline blurted. The matron put down her quill. “Miss

Stokes. You have been reprimanded twice." "I'm sorry. But —" "You will not say one more word unless addressed directly. Is that clear?" Evangeline nodded

miserably. The panic and worry that kept her vigilant all day had given way to an enervating torpor. She wondered, almost abstractly, if she might faint. Maybe she would. Merciful darkness

must be better than this. "Assault and theft,” the matron said to the constable, her hand on the page. “Those are the accusations?" "Yes, ma'am. And she is also . . .

with child.” "I see." "Out of wedlock, ma'am." "I understood your implication, constable.” She looked up. "So the charges are attempted murder and

larceny." He nodded. She sighed. “Very well. You may go. I'll escort the prisoner to the cells." Once the men had filed out, the matron inclined her head toward Evangeline.

“Long day for you, I suppose. I'm sorry to tell you it will not improve." Evangeline felt a rush of gratitude. It was the closest thing to kindness she'd experienced all day.

Tears gathered behind her eyes, and though she willed herself not to cry, they spilled down her cheeks. With her hands shackled, she couldn't wipe them away. For a few moments her

strangled sobs were the only sound in the room. "I need to take you down,” the matron said finally. "It wasn't like he said.” Evangeline hiccupped. “I — I didn't —"

"You are wasting your breath. My opinion is irrelevant.” "But I hate for you to . . . to think ill of me." The matron gave a dry laugh. “Oh, my girl. You are new to

this." "I am. Entirely." Setting down the quill and closing the ledger, the matron asked, “Was it force?" "Pardon?” Evangeline asked, uncomprehending. “Did a man

force himself on you?" "Oh. No. No." "It was love then, was it?” Sighing, the matron shook her head. “You're learning the hard way, Miss Stokes, that there's no

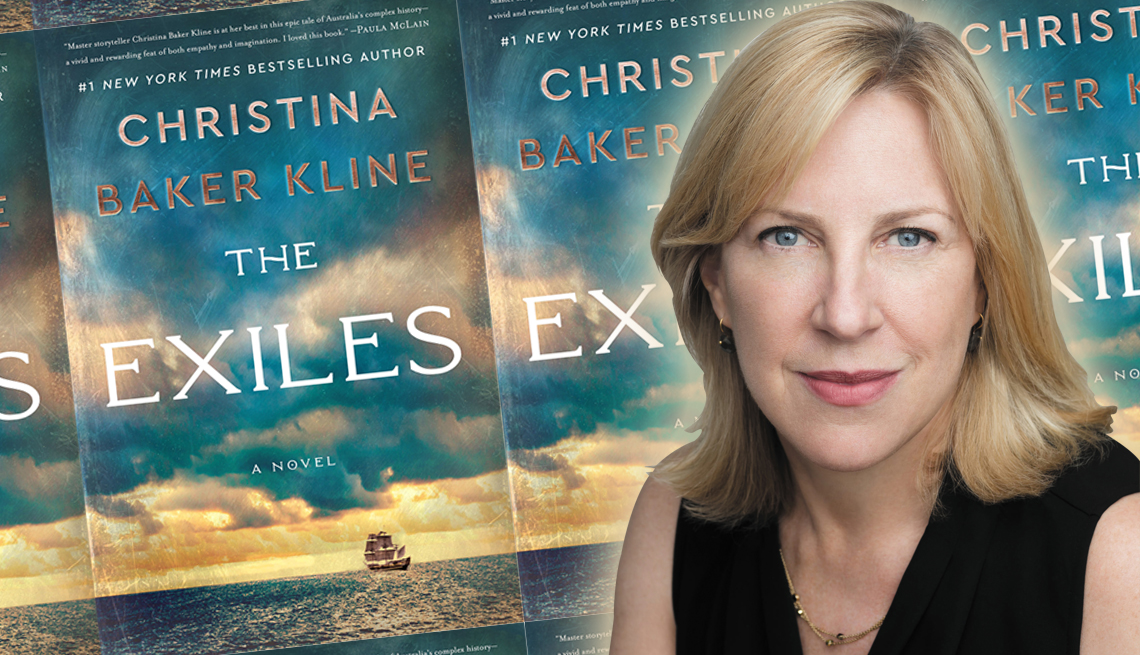

man you can count on. No woman neither. The sooner you understand that, the better off you'll be." _From THE EXILES by Christina Baker Kline Copyright © 2020 by Christina Baker

Kline. Reprinted by permission of Custom House, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers._ _Available at Amazon.com, Bookshop.org (where your purchase supports independent bookstores), Barnes

& Noble (bn.com) and wherever else books are sold._

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(764x349:766x351)/angela-90-day-fiance-121422-1-35189a463095429e901c4398d1f5f457.jpg)