- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

After an hour of circling the streets, she took refuge in the Covered Market. She bought a cup of hot chocolate and lingered near the stall to drink it. The man who’d been behind her in the

queue stood a few yards away. He kept glancing over. She pretended not to notice while taking in his five o’clock shadow, his dark hair skimming the collar of his faded denim jacket. He was

twenty. Maybe even twenty-five. When she left, he followed. She made it easy for him, stopping to look in the shop windows she had previously ignored, waiting for his reflection to join hers

before she moved on. In front of a shoe shop, he finally spoke. “You’re a hot little thing, aren’t you?” he said hoarsely. Close up, in full daylight, she saw that his eyes were bloodshot,

his nails arced with dirt, his clothes not faded but soiled. She ducked into the shop and tried on pairs of boots until it was time for the bus. Back in the street, she looked neither to

right nor left but ran all the way to the station. Only as she was queuing to board the bus did she dare to glance around. Her gaze fell on another man: fair hair, slightly haggard, standing

nearby. His gaze, quick, unsmiling, met hers. EIGHT MATTHEW “WILL YOU MAKE US A SIGN?” he said. “We’ll pay you the going rate.” He had been pleased when the idea came to him. Duncan would

feel appreciated, and the result would be much better than anything he or Benjamin could do. They were setting up a table outside the Co-op on Friday afternoon: _ARE YOU PREPARED FOR 2000?

HAVE YOU CHECKED YOUR LAWNMOWER?_ “Tell me what you want to say,” Duncan said. “Would you like pictures as well?” He was standing at his noticeboard, rearranging various postcards. His room,

as always, was the neatest in the house. “Pictures would be great. Maybe some of the appliances we’re demonstrating?” “Are things really going to fall apart on New Year’s Eve?” “No, it’s a

joke. Computers may go haywire, but staplers won’t. Can I see your new drawings?” Duncan straightened one last card and pulled out his large sketchbook. Setting it on the desk, he began to

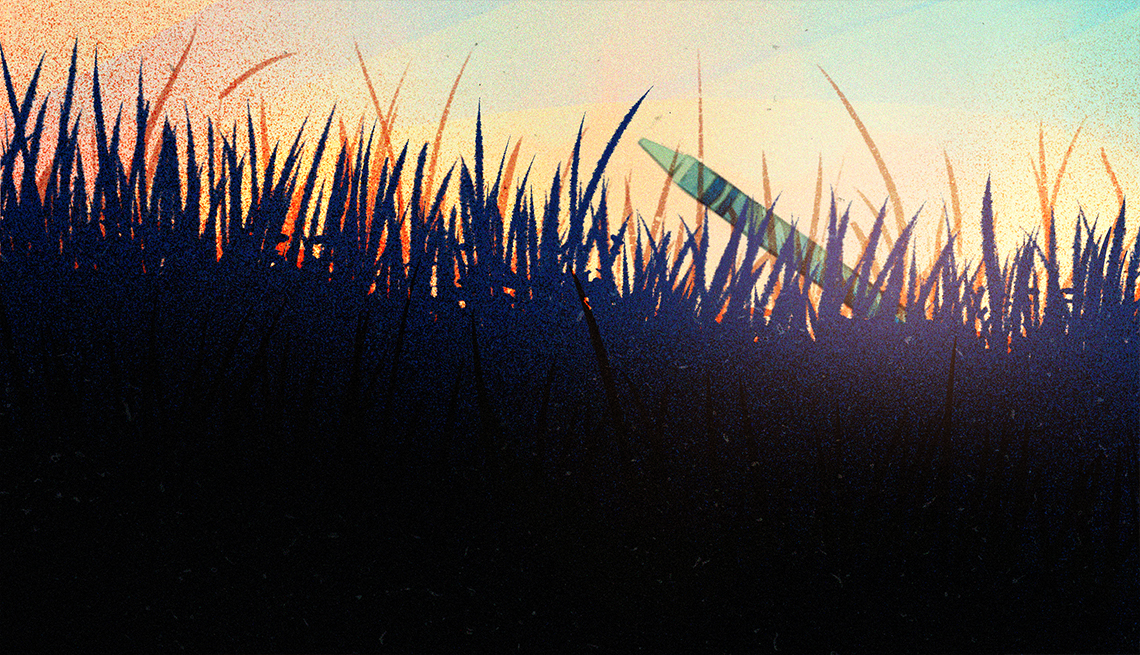

turn the pages. Here was his friend Will, his teacher Ms. Humphreys, the neighbor’s cat, their father’s workbench. He turned the page, and there was the boy, lying in the field. Matthew

heard his own sharp intake of breath. Beside him, he felt Duncan waiting for his reaction. He leaned closer, examining the boy’s quiet face, his bare bloody legs. The next page showed him

from a distance, a small, prone figure with a bale in the background. Yes, Matthew thought, he did look peaceful. He was torn between wanting to study each drawing and wanting to turn to the

next. “I remembered where I saw him before,” Duncan said. “Last spring I was waiting at the bus stop when he went by on his bike. He waved. I think he mistook me for someone else, but it

made me feel better about things.” By “things,” Matthew assumed Duncan meant how seldom he could answer the teachers’ questions. While Matthew was usually in the top three in his class, and

Zoe did well in subjects that interested her, his brother came twelfth, or fifteenth, except in art, but not because he was stupid. He had an amazing memory, and once he understood

something—Euclidean geometry, how to parse a sentence, the way hydrogen and oxygen bonded, why the repeal of the Corn Laws mattered—he remembered it precisely. “I’m following,” he had

explained to Matthew, “but then the teacher says electrons orbit each other, and suddenly I’m picturing them instead of listening.” Matthew bent to examine a drawing of Karel’s head, each

eyelash distinct, each link in the silver chain vivid. “This is exactly how I remember him,” he said. Duncan walked over to the window seat. When he turned around, he was holding a long,

straight knife with a wooden handle. Matthew recognized the carving knife that every month or two his mother or father wielded over a roast, and every five or six months his father took to

the forge to sharpen. “Last night,” Duncan explained, “I stabbed my mattress, to see if I could.”