- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT STUDY DESIGN: A repeated measures, non-randomised controlled trial. OBJECTIVE: To examine the effectiveness of individualised cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) on the psychological

adjustment of patients undergoing rehabilitation for newly acquired spinal cord injury. SETTING: South Australian Spinal Cord Injury Service, Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre, South

Australia, Australia. METHODS: Eleven participants received individual CBT as part of their spinal rehabilitation. Self-reported levels of depression, anxiety and stress were assessed before

the intervention, at week 12 of rehabilitation and at 3 months post-discharge, using the depression, anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21). Functional independence was also assessed, using

the Functional Independence Measure (FIM). Responses were compared with 13 participants, closely matched on demographic and injury variables, who received standard psychological care (that

is, assessment and monitoring only). RESULTS: Depression scores for treatment participants showed a significant time effect, with worsening symptoms reported at three-month follow-up, after

CBT was discontinued. In contrast, the DASS-21 scores of standard care participants remained at subclinical levels throughout the study. Clinical improvements in symptoms of anxiety and

stress were also reported by the treatment group as inpatient therapy progressed. CONCLUSION: Targeted, individualised psychological treatment contributed to short-term, meaningful

improvements in emotional outcomes for individuals reporting psychological morbidity after recent spinal injury. The results also highlight the need for ongoing access to specialised,

psychological services post-discharge. Replication of these results with a larger sample is required before definitive conclusions can be drawn. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE

INFLUENCE OF PSYCHOLOGICAL NEED ON REHABILITATION OUTCOMES FOR PEOPLE WITH SPINAL CORD INJURY Article 26 November 2022 THE SIR LUDWIG GUTTMANN LECTURE 2023: PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS AND

ADJUSTMENT DYNAMICS AFTER SPINAL CORD INJURY Article Open access 17 January 2025 REGAINING A SENSE OF ME: A SINGLE CASE STUDY OF SCI ADJUSTMENT, APPLYING THE APPRAISAL MODEL AND COPING

EFFECTIVENESS TRAINING Article 11 February 2021 INTRODUCTION The psychological impact of spinal cord injury (SCI) is significant, with 30% of patients showing clinical levels of anxiety

and/or depression during rehabilitation1 and after returning to community living.2 Research suggests that specialist psychological interventions have a role in managing these emotional

outcomes.3, 4 Research also indicates that the provision of psychotherapy in spinal rehabilitation is constrained by a number of factors, including workforce issues, with limited staff

resources often only allowing for a consultative service instead of comprehensive psychological assessment and intervention,5 and service delivery models that emphasise time-limited

therapy.6, 7 Although group-based programmes using cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) have been advocated as a time-efficient inpatient therapy model,3, 4 their effectiveness is influenced

by group homogeneity, with regard to patient characteristics.8 There is also evidence that patients prefer individual counselling when discussing emotive issues.9 This suggests that group

CBT should augment, rather than replace, individual therapy. In light of these issues, we undertook a small-scale study to evaluate the discipline-specific contribution of psychology to

rehabilitation outcomes in patients with newly acquired SCI. This was achieved by comparing self-reports of patients who received psychological intervention with those of matched peers who

required less intensive psychological support. It was expected that individual-based CBT, similar to previous group trials, would be of therapeutic benefit. However, it was not known whether

any such benefit would be maintained after being discharged from an inpatient setting and in the absence of continued CBT. MATERIALS AND METHODS PARTICIPANTS Participants were adults (⩾18

years) with English comprehension (at least primary school level education), who were undergoing rehabilitation at the Spinal Injuries Unit of Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre. Only

individuals with a newly acquired injury, no pre-morbid psychiatric illness (such as substance abuse or psychosis diagnosed in the last 12 months) and no significant cognitive deficits

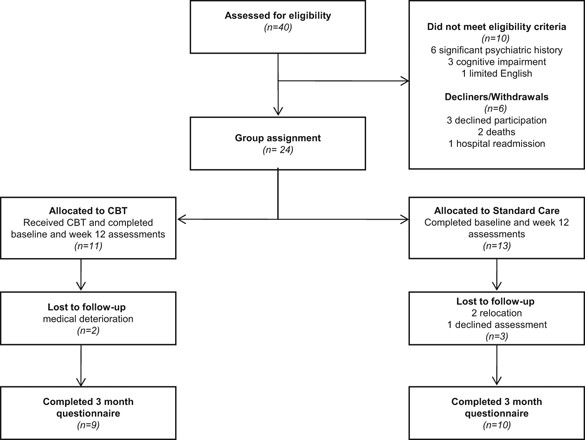

sufficient to interfere with therapy participation, as determined by medical report, were included. Participants were recruited on a prospective basis over an 18-month period. Details of

participant selection and group allocation are provided in Figure 1. The final sample of 11 treatment and 13 standard care participants met the minimum required to achieve a large effect

size of 0.80 for a two-tailed test with 90% power at a 0.05 significance level.10 MEASURES A standard measure, the functional independence measure (FIM),11 was used to assess disability

severity. The FIM was carried out on a person's admission and discharge date, with ratings determined by a team of allied health, nursing and medical staff. The FIM consists of 18 items

that address motor and cognitive aspects of function. Items are scored on a 7-point scale that ranges from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (complete independence), with total scores ranging from

18 to 126. Higher scores indicate a lower severity of disability. The FIM shows good evidence of reliability and validity and is routinely used in spinal rehabilitation.12 The depression,

anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21)13 were administered on an individual's admission to the Unit. This 21-item questionnaire, derived from the original 42-item DASS, consists of three

subscales designed to measure the emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress. Each subscale contains seven items scored on a 4-point scale that ranges from 0 (‘Did not apply to me at

all’) to 3 (‘Applied to me very much’). Subscale scores are summed and multiplied by two to allow comparison with normative values. The subscale scores can also be added to produce a

composite measure of distress, with a score range from 0 to 126. Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress. The DASS-21 has been shown to be a sensitive

indicator of mood in people with SCI.14 PROCEDURES Written informed consent was sought to access FIM and DASS-21 scores before psychological intervention (Time 1) and to re-administer at

two additional time intervals: at week 12 (Time 2) of an individual's rehabilitation program or on discharge, if earlier (average Time 2 interval=11.3 weeks, s.d.=2.1), and at three

months post-discharge (Time 3; DASS-21 only). The standard care group was tested at the same time intervals. A clinical psychologist (DSD) was responsible for study recruitment. Although a

detection bias is added by having one investigator allocate participants and deliver the intervention, this was unavoidable as the study was based in a single clinical setting that employed

only one psychologist. Importantly, this clinician was not involved in assessing outcomes, with the FIM determined by other professionals and the DASS-21 based on self-report, thereby

minimising any potential bias. Participants were drawn from consecutive admissions to the Spinal Injuries Unit. Study eligibility was determined during the patient's routine screen with

the psychologist. This assessment, which involved clinical interview and baseline measurement (including the DASS-21), determined the treatment decision. Those who reported elevated levels

of distress (that is, DASS-21 scores in the moderate-to-severe range) were offered individual CBT. This subgroup was targeted for intervention as research suggests that individuals with

clinically significant levels of distress are at risk of poor, long-term emotional outcomes and are a priority for psychological treatment.2, 3 In comparison, patients who reported DASS-21

scores in the subclinical range, and who met the same inclusion criteria, were assigned to the standard care group. These participants were also screened to match the treatment group on age,

sex and injury. Participants in the standard care group continued to be monitored by the Unit's medical team and could withdraw from the study if their psychological treatment needs

increased. Individuals who declined study participation or were ineligible were still offered individual CBT during their rehabilitation. TREATMENT Therapy followed a cognitive behaviour

model that has shown efficacy in SCI groups.3, 4 The CBT was delivered by the Unit's clinical psychologist (DSD) and provided in addition to physical therapies. Therapy was guided by

patients' psychological problems and treatment response but was also affected by physical rehabilitation schedule conflicts. On average, treatment participants received 11 CBT sessions

(s.d.=4.5; range from 7 to 22 sessions). This involved fortnightly consultations of 30–60 min duration with the psychologist. There was a positive relationship between length of

rehabilitation stay and amount of psychotherapy received (_r__s_=0.44, _P_=0.031), with longer admissions allowing more opportunity for intervention. Owing to limited staffing, CBT was only

offered to patients in the rehabilitation setting, with psychology services not readily available in the acute or community settings. The key treatment goals were: to build individuals'

confidence regarding the benefits of receiving CBT, education about the emotional impact of SCI, relieve symptoms of stress and the development of coping skills (including problem-solving

strategies, behavioural activation and cognitive appraisal skills). In addition, peer professionals were available to all participants to provide mentoring. Peers are thought to have a

critical role in spinal rehabilitation, with peer involvement contributing to improved emotional outcomes including self-esteem and social support.15 Psychiatric evaluation was also required

for five treatment participants who reported severe distress. Low-dose amitriptyline was prescribed to these participants, as well as to five participants in the standard care group, for

night-time sedation and to manage neuropathic pain. DATA ANALYSIS Median and interquartile ranges were used to examine variability in group DASS-21 scores. Median, rather than mean, scores

were reviewed because the data were not normally distributed. Given that the treatment and standard care groups had differing prognoses, with more severely distressed persons allocated to

CBT, the two groups were evaluated separately. As the data did not meet the stringent requirements of parametric techniques, non-parametric statistics were used. The Friedman's analysis

of variance and Wilcoxon's matched-pairs signed ranks test were considered the most appropriate statistical methods to determine the effectiveness of CBT. Significant within-group

differences would have been difficult to achieve due to the small sample size, even with clinically meaningful improvements in mood due to treatment.16 Therefore, treatment efficacy was also

evaluated using Cohen's _d_ effect sizes, based on the formula provided by Morris and DeShon.17 As a guideline, Cohen's _d_ values of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 equate to small, medium and

large group differences, respectively.18 The direction of effect was standardised so that a positive effect indicated that CBT was beneficial to outcome and a negative effect indicated an

undesirable outcome. STATEMENT OF ETHICS All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this

research. RESULTS SAMPLE COMPARABILITY The final sample of 24 participants was found to be comparable to those who either declined to participate or withdrew before study commencement

(_n_=6) in terms of gender (83 male vs 67%, Fisher's Exact test=0.57; Cramer's _V_=0.17; _P_>0.05) and injury type (58% with paraplegia vs 67%, Fisher's Exact test=1.00;

Cramer's _V_=0.07; _P_>0.05). Although these groups did not differ significantly in age (_U_=49.00, _Z_=1.19, _P_>0.05, Cohen's _d_=0.66), the moderate effect size indicates

that the final sample was older (on average, 13.6 years older). The sample demographics were also compared to the Unit's admission statistics to determine whether these results were

likely to be generalisable to the larger group of SCI patients. There were no significant group differences in age (_t_(80)=0.16; _P_>0.05; _d_=0.04), gender (83% male vs 67%;

_χ_2(1)=2.18; _P_>0.05) or injury severity (58% with paraplegia vs 57%; _χ_2(1)=0.10; _P_>0.05), suggesting that the study sample was representative of the broader group of patients

admitted to the Unit. PARTICIPANTS The study sample was almost exclusively male (83%; Table 1) and all participants were Caucasian. The largest percentage had completed high school (63%),

followed by tertiary qualifications (25%). Most were employed (63%) and a higher percentage of individuals were single (58%) at the time of their injury. In terms of their injury details

(Table 1), the treatment and standard care groups did not differ significantly on injury type or lesion severity. Both traumatically acquired injuries (for example, falls, motor vehicle

accidents) and non-traumatic injuries (for example, spinal abscess) occurred. FUNCTIONAL REHABILITATION OUTCOMES There were no significant differences between the treatment and standard care

groups in terms of their length of hospital or rehabilitation stay (Table 1). Although there was a trend for those in the treatment group to have had longer acute admissions (by

approximately 33 days), this difference was not significant. Functional rehabilitation outcomes were also similar for the groups (see Table 1), with no significant differences in mean total

FIM scores on admission or at discharge. Moreover, the associated effect sizes were small (_d_admission=0.27, _d_discharge=0.19). Total FIM scores did not correlate significantly with total

DASS-21 scores at admission (_r__s_=0.04; _P_>0.05) or discharge (_r__s_=−0.03; _P_>0.05), suggesting that functional state and mood were not strongly related. The employment rate

post-injury was low, with only two participants returning to work after being discharged. This figure may have been a reflection of either the older age range of participants, with 33%

(_n_=8) having retired before their injury, or of their ongoing rehabilitation needs, with 54% (_n_=13) continuing to receive outpatient physical therapy at final follow-up. DEPRESSION,

ANXIETY AND STRESS OUTCOMES Table 2 summarises the median scores on the DASS-21 for the sample at each of the three time points. As expected, the treatment group reported significantly

higher subscale and total DASS-21 scores at each time point, and greater variability in these scores, as evident in the large interquartile ranges. The results of the Friedman analyses of

variance (Table 2) demonstrated significant differences in the depression scores for treatment participants across time, but no differences in their DASS-21 total scores or associated

anxiety and stress subscale scores. The DASS-21 scores for the standard care group did not change significantly over time (see Table 2). _Post-hoc_ analyses for the treatment group (Table 3)

showed a decline in the levels of depression from baseline to week 12 of treatment, although this equated to only a very small effect (_d_=0.08). In contrast, there was a significant

increase in depressive symptomatology at three-month follow-up (_d_=−0.68). Similarly, total DASS-21 scores and subscale scores for anxiety and stress, declined from baseline to week 12 and

were associated with moderate, positive effect sizes (total DASS-21 _d_: 0.38, anxiety _d_: 0.50; stress _d_: 0.48). At three-month follow-up, treatment participants reported a significant

increase in levels of general distress and anxiety. The clinical impact of these findings is highlighted by additionally examining individual ‘caseness’. Of the six treatment participants

who reported clinical anxiety at baseline, two reported a reduction in symptom severity (that is, from extremely severe to the moderate or mild range) and two reported a complete resolution

of symptoms. Similarly, all three treatment participants who initially reported moderate to severe stress symptoms subsequently reported only mild levels of stress at week 12. In terms of

depressive symptoms, two of four treatment participants reported symptom improvement at week 12 and this clinical change was significant (_χ_2(1)=6.67; _P_=0.048). The three-month follow-up

data are particularly revealing. Post-discharge, when there was no access to continued psychological support, 78% (_n_=7) of the treatment participants met the criteria for caseness on one

or more DASS-21 subscales compared with 10% (_n_=1) of the standard care group. A χ2 analysis showed that this percentage change was significant (_χ_2(1)=8.93; _P_=0.005). DISCUSSION This

small-scale study examined the impact of individual CBT in an inpatient SCI rehabilitation setting when compared with less intensive psychological support. Not surprisingly, there was large

within-group variability in the levels of psychological distress reported by treatment participants. The study results also highlight the variable impact of CBT on a subgroup of individuals

reporting severe symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress at baseline. Depression scores improved with CBT and then significantly declined, post-intervention, in the treatment group. There

were associated improvements in DASS-21 caseness for this group. In comparison, there was no significant time effect on the DASS-21 for participants receiving standard care. To an extent,

these results mirror previous research on the effectiveness of CBT after SCI. The finding that distress levels of treatment participants were severe at the commencement of rehabilitation

reinforces the need for psychological intervention in the acute stages of SCI management.1 With self-reported distress levels increasing post-discharge, the continued mental health needs of

this patient group are also evident.1, 19 These results need to be interpreted in light of the methodological difficulties. Power analyses (Table 3) indicate that the study was underpowered.

As such, small treatment effects, which were more achievable, would have been difficult to detect.10, 18 Replication of the study with a larger sample is therefore essential. The timing of

assessments may have also affected the results. Some treatment participants had not completed their inpatient rehabilitation and, subsequently, their CBT program at the week-12 assessment.

Higher treatment gains may have been observed if outcome was assessed immediately post-intervention. Another limitation relates to the highly selected sample. Participants in the standard

care group reported different levels of psychological distress at baseline, reducing the equivalence of the two groups. However, building the patient triage process into the CBT package also

acknowledged the practical aspects of delivering a service in a clinical setting with limited staff resources.6 This preliminary study highlights the difficulties encountered in clinical

trials, in terms of methodology and availability of participants. The CBT was dependent on limited staff resources, which impacted on therapy frequency and duration. This may, therefore, not

have been the optimal treatment for the severity of problems reported. Although the efficacy of CBT was reinforced by accessing peer role models and liaison psychiatry, improvements in the

service strategy could include a stepped-care service model,20 with psychological intervention commencing in the acute setting and including access to specialised outpatient services to

prevent psychological relapse. CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare no conflict of interest. REFERENCES * Craig AR, Tran Y, Middleton J . Psychological morbidity and spinal cord injury:

a systematic review. _Spinal Cord_ 2009; 47: 108–114. Article CAS Google Scholar * Pollard C, Kennedy P . A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic

psychological growth following spinal cord injury. _Br J Health Psychol_ 2007; 12: 347–362. Article Google Scholar * Craig AR, Hancock K, Dickson H, Chang E . Long-term psychological

outcomes in spinal cord injured persons: results of a controlled trial using cognitive behaviour therapy. _Arch Phys Med Rehabil_ 1997; 78: 33–38. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kennedy P,

Duff J, Evans M, Beedie A . Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injury. _Br J Clin Psychol_ 2003; 42: 41–52. Article CAS Google

Scholar * Burton C, Murphy G, Smith-Tappe G . _Workforce Survey of Psychologists in the Rehabilitation Sector—Victoria_. The Australian Psychological Society Ltd: Melbourne, 2005. Google

Scholar * Schwartz SM, Shanmugham K, Trask PC, Townsend CO . Conducting psychological research in medical settings: Challenges, limitations and recommendations for effectiveness research.

_Prof Psychol Res Pr_ 2004; 35: 500–508. Article Google Scholar * Schutz LE, Rivers KO, Ratusnik DL . The role of external validity in evidence-based practice for rehabilitation. _Rehabil

Psychol_ 2008; 53: 294–302. Article Google Scholar * Huebner RA . Group Procedures. In: Chan F, Berven NL, Thomas KR (eds.). _Counseling theories and techniques for rehabilitation health

professionals_. Springer Publishing Company: New York, 2004, pp 244–263. Google Scholar * Schoenberg M, Shiloh S . Hospitalised patients' views on in-ward psychological counselling.

_Patient Educ Couns_ 2002; 48: 123–129. Article Google Scholar * Kraemer HC, Thiemann S . _How Many Subjects? Statistical Power Analysis in Research_. Sage Publications: Newbury Park,

1991. Google Scholar * Hamilton BB, Granger CV, Sherwin FS, Zeilezny M, Tashman JS . Uniform national data system for medical rehabilitation. In: Fuhrer MJ (ed). _Rehabilitation outcomes:

Analysis and measurement_. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company: Baltimore, MD, 1987, pp 137–147. Google Scholar * Dawson J, Shamley D, Jamous MA . A structured review of outcome measures

used for the assessment of rehabilitation interventions for spinal cord injury. _Spinal Cord_ 2008; 46: 768–780. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF . _Manual for the

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales_, 2nd ed Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, 1995. Google Scholar * Mitchell MC, Burns NR, Dorstyn DS . Screening for depression and anxiety in

spinal cord injury with DASS-21. _Spinal Cord_ 2008; 46: 547–551. Article CAS Google Scholar * Middleton J, Craig AR . Psychological challenges in treating persons with spinal cord

injury. In: Craig AR, Tran Y (eds). _Psychological Dynamics Associated with Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: New Directions and Best Evidence_. Nova Science Publishers: New York, 2008, pp

1–47. Google Scholar * Zakzanis KK . Statistics to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth: formulae, illustrative numerical examples, and heuristic interpretation of

effect size analyses for neuropsychological researchers. _Arch Clin Neuropsychol_ 2001; 16: 653–667. Article CAS Google Scholar * Morris SB, DeShon RP . Combining effect size estimates in

meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. _Psychol Methods_ 2002; 7: 105–125. Article Google Scholar * Cohen J . A power primer. _Psychol Bull_ 1992; 112:

155–159. Article CAS Google Scholar * Migliorini C, Tonge B, Taleporos G . Spinal cord injury and mental health. _Aust NZJ Psychiatry_ 2008; 42: 309–314. Article Google Scholar *

O'Donnell ML, Bryant RA, Creamer M, Carty J . Mental health following traumatic injury: Toward a health system model of early psychological intervention. _Clin Psychol Rev_ 2008; 28:

387–406. Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the patients and staff at Hampstead Rehabilitation Centre for their cooperation. We also thank Prof Tonge and

Dr Taleporos, Monash University, for their contribution to the study's design. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * South Australian Spinal Cord Injury Service, Hampstead

Rehabilitation Centre, Northfield, South Australia, Australia D S Dorstyn * School of Psychology, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia D S Dorstyn, J L Mathias &

L A Denson Authors * D S Dorstyn View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * J L Mathias View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * L A Denson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to D S Dorstyn. RIGHTS

AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Dorstyn, D., Mathias, J. & Denson, L. Psychological intervention during spinal rehabilitation: a preliminary

study. _Spinal Cord_ 48, 756–761 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.161 Download citation * Received: 09 May 2009 * Revised: 20 October 2009 * Accepted: 20 October 2009 * Published: 22

December 2009 * Issue Date: October 2010 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.161 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS *

depression * anxiety * stress * rehabilitation * cognitive behavioural treatment

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/matt-james-tyler-cameron3-da87d1da8e42453abc8da92a595796cf.jpg)